Professor at FGV-EAESP I Researcher at NEOP FGV-EAESP I AOM-MED Ambassador I Postdoctoral Fellow in the Psychiatry Graduate Program at USP

14 Ekim 2025

Abstract

This study examines patterns of scientific productivity, impact, visibility, and collaboration in the field of Business and Management across the BRICS countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—using data from the AD Scientific Index (2025). Building on the literature on the knowledge economy and global academic hierarchies, the article explores how emerging knowledge systems negotiate their position within an increasingly metric-driven landscape dominated by the North Atlantic rankings. The AD Scientific Index, by adopting a bottom-up approach based on individual researcher profiles drawn from Google Scholar Citations, offers a broader and more inclusive view of scientific performance, particularly suited to the applied social sciences. Employing a descriptive-comparative design and secondary data analysis, the study constructs a multidimensional framework encompassing five analytical dimensions—productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality—and applies descriptive statistics, non-parametric comparisons, and network analysis to institutional and individual data. Results reveal a heterogeneous configuration: China and India lead in productivity and citation impact; Brazil and South Africa combine moderate output with strong social relevance and open-access dissemination; and Russia exhibits concentrated excellence within a limited set of institutions. Despite rapid expansion, all five countries display high internal inequality in the distribution of academic prestige and visibility. The findings suggest that BRICS management research operates through hybrid regimes that blend global competitiveness with contextual engagement, contributing to the pluralization of epistemic centers within the global knowledge economy.

Keywords: Scientometrics; Management Research; Knowledge Economy; Epistemic Pluralism; BRICS

https://www.adscientificindex.com

Introduction

The evaluation of scientific productivity has become a central element in the construction of academic reputation, the formulation of institutional strategies, and the allocation of research resources worldwide. Over the past two decades, global ranking systems such as Times Higher Education (THE), QS World University Rankings, and Scimago Institutions Rankings have consolidated their position as benchmarks for comparing universities, relying primarily on bibliometric indicators derived from databases such as Scopus and Web of Science. By emphasizing publication volume, citation counts, and international collaboration, these instruments have shaped prevailing expectations of scientific excellence. However, in the social sciences—and particularly in the field of Management—such rankings have been increasingly criticized for favoring standards typical of the “hard sciences,” thereby underestimating outputs such as books, case studies, and applied publications in local languages that are central to the contextual and practice-oriented nature of management research. Moreover, recent studies confirm that conventional rankings tend to reproduce historical institutional privileges and exacerbate territorial and linguistic asymmetries in academic visibility (Hamann, 2023).

Against this background, the AD Scientific Index (2025) emerges as an alternative and increasingly relevant tool for understanding the global distribution of scientific performance. Rather than relying solely on aggregate institutional outcomes, it adopts a bottom-up perspective by constructing metrics from the individual profiles of researchers using Google Scholar Citations. This approach expands the analytical scope by incorporating a wider range of academic contributions—including open-access publications, working papers, and non-English outputs—that are often excluded from traditional databases. Such inclusiveness and multidimensionality are particularly relevant to the applied social sciences and to the field of Management, where impactful research frequently extends beyond indexed journal articles to include case-based learning materials, professional reports, and context-specific analyses.

The scientific expansion of the BRICS countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—illustrates the importance of this more plural perspective. Representing nearly 40% of the global population and producing an expanding share of the world’s scientific output, these nations are reshaping the geography of knowledge production. Yet their trajectories remain heterogeneous. China continues to consolidate its leadership, representing over 45% of total BRICS publications and more than half of all citations in Business and Management fields, followed by India, which displays robust doctoral networks and institutional diversification. Brazil maintains a distinctive profile characterized by high research engagement in the social sciences and public policy, sustained by state-funded universities and strong regional collaboration networks. Russia’s scientific ecosystem remains more centralized, with high-impact production concentrated in a few elite institutions such as the Higher School of Economics and Lomonosov Moscow State University. South Africa, in turn, combines moderate output with strong international partnerships, particularly with European and other African universities.

The choice of the AD Scientific Index for this study is therefore justified by its ability to capture these differentiated trajectories and reveal the patterns of productivity, visibility, and collaboration that emerge at the intersection of national academic cultures and global evaluation regimes. By integrating Google Scholar, h-index, and i10-index metrics, the index enables an assessment that combines cumulative impact with performance consistency and inclusivity. Its bottom-up methodology accommodates diverse forms of scientific contribution—many of which remain invisible to citation-based metrics used by Scopus and Web of Science—and thereby offers a more equitable framework for evaluating excellence in the Global South. Consequently, it provides a suitable analytical instrument for examining configurations of excellence and institutional hierarchy within BRICS countries in the field of Management.

This study thus aims to investigate the patterns of scientific productivity, visibility, and collaboration among institutions and researchers in the BRICS nations as reflected in the AD Scientific Index (2025). Specifically, it seeks to identify the most prominent universities and scholars in Management in each country, to compare impact and citation indicators across nations, and to analyze the asymmetries that characterize their evolving research ecosystems. By situating these comparisons within the broader dynamics of the global stratification of knowledge, the article contributes to a more nuanced understanding of how emerging knowledge economies negotiate their position within the international academic system.

The following section develops the theoretical framework that supports this investigation, exploring contemporary debates on global rankings, critiques of bibliometric evaluation systems, and the political economy of knowledge production in emerging contexts.

Theoretical Framework

The emergence of the knowledge economy has profoundly redefined the foundations of national competitiveness and institutional development, positioning scientific production as both a driver and a reflection of broader socioeconomic transformations. Since the late twentieth century, knowledge has come to be understood not merely as a resource but as a productive force in itself—central to innovation, governance, and organizational strategy (Foray, 2018; Lundvall, 2010). Within this paradigm, universities and research centers assume a dual role: they act as generators of scientific capital and as agents of economic and social development, mediating the flow of ideas, technologies, and competencies across sectors. Yet, as contemporary analyses emphasize, the knowledge economy is not a homogeneous global field but a differentiated and stratified landscape structured by asymmetries in resources, infrastructure, and institutional capacity (Cantwell & Marginson, 2018).

The global system of science now operates within what has been described as a multi-scalar hierarchy, in which central and peripheral positions are reproduced through flows of prestige, funding, and recognition (Mosbah-Natanson & Gingras, 2014). Core economies—particularly those of the North Atlantic—continue to dominate high-impact journals, editorial boards, and international research collaborations. Emerging economies, in turn, often remain dependent on epistemic standards and evaluative models established elsewhere, perpetuating what Alatas (2003) and Connell (2019) term academic dependency. This phenomenon, reinforced by linguistic and infrastructural barriers, limits the global visibility of alternative epistemologies and locally grounded research. In management studies, this imbalance manifests in the dominance of Anglo-American theoretical paradigms and in the concentration of top-tier journals indexed in the Web of Science and Scopus, which privilege English-language publications and quantitative methodologies (Tourish, 2020; Boussebaa & Tienari, 2021).

Recent scholarship, however, points to a gradual diversification of knowledge geographies and a partial erosion of traditional hierarchies. Emerging knowledge systems—particularly in the BRICS—are expanding their academic presence by developing hybrid configurations that combine state-led investment, international partnerships, and institutional reforms designed to strengthen higher education and research ecosystems (UNESCO, 2021). Scientific development in these contexts cannot be reduced to imitation of Western models; rather, it reflects adaptive processes that integrate local priorities—such as inclusive growth, sustainability, and technological sovereignty—into globally competitive frameworks. China and India, for example, have consolidated strategic research clusters with strong links between academia and industry, while Brazil and South Africa continue to anchor their scientific production in socially oriented and regionally embedded universities.

Within the applied social sciences—and especially in Business and Management—these transformations reveal a shifting epistemic landscape. Historically, management research has been structured by institutional hierarchies centered around North American and European schools of thought, where publication in a restricted set of elite journals functions as a mechanism of epistemic gatekeeping (Tourish, 2020). The globalization of education and the digitalization of knowledge dissemination, however, have expanded the space for alternative academic communities, enabling South–South collaborations and open-access initiatives that challenge the dominance of traditional centers (Boussebaa & Tienari, 2021; Ibarra-Colado, 2006). The increasing visibility of scholarship from Latin America, Asia, and Africa signals a gradual reconfiguration of how legitimacy and scientific authority are distributed within the field.

This broader reorganization of scientific production has been accompanied by the institutionalization of what Moed (2017) calls evaluative informetrics—the use of quantitative indicators not merely to measure but to shape academic behavior and institutional strategies. The proliferation of scientometric instruments such as Scimago, Google Scholar Metrics, and, more recently, the AD Scientific Index (2025), exemplifies how quantification has become an essential element of the global knowledge economy. Metrics no longer serve solely descriptive functions; they act performatively, influencing funding allocations, hiring criteria, and international collaborations (Wouters, 2014; Hicks et al., 2025). While these tools enhance transparency and comparability, their adoption in emerging contexts remains ambivalent: they provide global visibility yet risk reinforcing dependence on evaluative regimes that undervalue locally relevant, interdisciplinary, and socially engaged research (Shen & Ma, 2022).

Understanding the knowledge economy in the twenty-first century therefore requires moving beyond linear models of innovation and diffusion to recognize the plural, networked, and contested nature of global science. The interplay between global hierarchies and national systems of knowledge production constitutes a critical analytical frontier for examining how the BRICS navigate their position within this evolving landscape. Their trajectories demonstrate that scientific modernization is not merely a technical or institutional endeavor but a deeply political and cultural process that redefines what counts as legitimate and valuable knowledge. This theoretical orientation provides the foundation for the present study, which employs the AD Scientific Index (2025) as an analytical lens to examine how the structural asymmetries of the global knowledge economy manifest within the field of Business and Management across the BRICS countries. By situating empirical findings within this broader conceptual framework, the analysis seeks to illuminate both the persistence of global scientific hierarchies and the emerging possibilities for epistemic pluralism and institutional differentiation in management research.

Rankings and Scientometric Indicators

The proliferation of global university rankings over the past two decades has profoundly transformed how scientific performance is perceived, valued, and managed. Rankings such as Times Higher Education (THE), QS World University Rankings, Scimago Institutions Rankings, and, more recently, the AD Scientific Index, have become powerful instruments of academic governance, reshaping institutional behavior and the organization of research systems worldwide (Hicks et al., 2025). These instruments emerged within a broader landscape characterized by market-oriented reforms and heightened accountability pressures in higher education, where the quantitative assessment of productivity, impact, and visibility serves not only as a diagnostic tool but also as a mechanism of symbolic capital accumulation (Sauder & Espeland, 2009). Consequently, universities increasingly align their strategies with ranking metrics, as institutional positioning now influences funding allocations, international partnerships, and the recruitment of talent, thereby reinforcing the performative power of these evaluation systems (Wilsdon et al., 2022).

Among the most consolidated frameworks, the Times Higher Education (THE) World University Rankings integrates five dimensions: teaching quality, research volume and reputation, citation impact, international outlook, and industry income. While recognized for methodological transparency, its reliance on Scopus data and self-reported institutional information introduces linguistic and regional biases that structurally favor universities from the Global North. Similarly, the QS World University Rankings continues to emphasize reputation-based indicators, assigning nearly 50% of its weighting to academic and employer perception surveys (QS Quacquarelli Symonds, 2024). This emphasis on subjective prestige reproduces cumulative advantage effects, consolidating the dominance of historically established institutions and limiting the mobility of emerging universities. The Scimago Institutions Rankings (SIR), based on Scopus bibliometric data, adopts a more empirical approach structured around three dimensions—research performance, innovation, and societal impact. Its multidimensional classification offers a partial correction to concentration effects observed in reputation-driven models, yet it remains anchored in data sources that underrepresent outputs from the social sciences, local journals, and non-English publications.

As a result, the epistemic architectures of conventional rankings continue to privilege publication formats and citation practices aligned with Anglo-American scientific norms. Hammarfelt and Rushforth (2017) describe this phenomenon as epistemic governance through indicators—a process in which metrics not only measure but also prescribe legitimate forms of knowledge production. In Business and Management, this has entrenched a narrow conception of academic excellence based on the Financial Times 50 and ABS Journal Quality List, reinforcing the hegemony of Western epistemologies and constraining the visibility of scholarship from emerging regions (Tourish, 2020; Adler & Harzing, 2022).

Within this contested landscape, the AD Scientific Index introduces an alternative epistemological orientation and methodological logic. By focusing on individual researchers rather than institutions, it constructs a more decentralized and inclusive representation of scientific productivity. The index aggregates data from Google Scholar Citations, computing total citations, h-index, and i10-index for each scholar, while also providing institutional and national aggregates. Its innovation lies in inclusivity: Google Scholar captures a broader spectrum of academic outputs—books, reports, open-access publications, and local-language works—that are often excluded from mainstream databases (Orduña-Malea et al., 2020). This approach allows for cross-sectional comparisons within and between countries, revealing intra-institutional disparities, disciplinary hierarchies, and emerging collaboration patterns, particularly within the Global South.

However, this inclusivity also entails methodological challenges. The absence of standardized peer-review validation and the self-maintained nature of Google Scholar profiles introduce variability and potential inconsistencies in citation data (Aguillo, 2023). Additionally, differences in disciplinary citation practices and the inclusion of non-scholarly materials can lead to overestimation in certain contexts (Hicks et al., 2025). Yet despite these limitations, the AD Scientific Index (2025) has gained increasing recognition as a complementary system to traditional rankings, particularly valuable for mapping the diversity of scientific ecosystems in emerging economies. For the BRICS, it provides an analytical lens through which to observe the pluralization of publication formats, the democratization of scholarly visibility, and the rise of non-traditional forms of impact in applied fields such as Business and Management.

The coexistence of these systems underscores a deeper epistemological tension within contemporary scientometrics. While rankings aspire to objectivity and standardization, they inevitably reflect sociotechnical judgments about what constitutes valuable knowledge and who holds authority to define excellence (Wouters, 2014; Hicks et al., 2025). In the field of Management, these dynamics are particularly salient: publication in a narrow corpus of Western-controlled journals functions as a symbolic currency that simultaneously enables global legitimacy and constrains epistemic diversity. As research production from the BRICS expands in both volume and scope, the interplay between international rankings and national evaluation systems becomes a critical site for negotiating recognition and reconfiguring the hierarchies of academic prestige. Understanding the methodological logics, biases, and performative effects of these systems is therefore essential for interpreting the empirical results that follow, as rankings not only describe the global landscape of scientific productivity but actively shape the practices through which knowledge is produced, circulated, and valued.

BRICS and Scientific Collaboration

Scientific collaboration has long been recognized as a cornerstone of global knowledge production, serving simultaneously as a mechanism for capacity building and as a driver of epistemic integration across national systems. Within the BRICS countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—collaborative research has become a key strategy for enhancing scientific visibility, leveraging comparative advantages, and reducing structural dependencies on institutions from the Global North. Over the past two decades, the BRICS alliance has progressively institutionalized cooperation in science, technology, and innovation through frameworks such as the BRICS Science, Technology and Innovation Framework Programme (2015) and the BRICS Network University, both designed to promote mobility, joint funding, and transdisciplinary collaboration. These initiatives reflect a shared aspiration to consolidate an autonomous scientific identity capable of engaging with, and transforming, global epistemic hierarchies.

The consolidation of BRICS scientific collaboration reflects a dual dynamic. On one hand, it embodies pragmatic interests in resource sharing, technology transfer, and human capital development; on the other, it represents a symbolic and strategic effort to challenge the epistemological asymmetries embedded in the international research system. Despite differences in political regimes, economic models, and institutional maturity, all five nations share a long-term commitment to expanding research infrastructure and aligning scientific agendas with national development goals. China, for instance, has consolidated its role as a global research leader through sustained investment in higher education and innovation ecosystems, with over 2.5 million publications indexed in Scopus by 2025 and a marked increase in cross-border co-authorship (Zhou, 2020; UNESCO, 2021). India continues to strengthen its internationalization strategy through diversified partnerships and a growing body of research in technology and management studies, with its top institutions—such as the Indian Institutes of Management and the Indian School of Business—gaining prominence in global rankings. Brazil, despite chronic funding fluctuations, maintains a dense and resilient network of collaborations in the social sciences and applied management fields, supported by public universities and graduate programs. Russia and South Africa, though differing in scale and orientation, have similarly prioritized international partnerships as mechanisms for revitalizing scientific capacity and increasing visibility (Glänzel et al., 2019).

Collaboration within the BRICS, however, is far from uniform. Scientometric analyses based on 2025 data reveal that while China and India dominate in terms of publication volume and citation impact, Brazil and South Africa contribute disproportionately to research addressing social innovation, governance, and sustainability. Russia, by contrast, remains primarily oriented toward the fundamental sciences and engineering, maintaining continuity with its Soviet-era academic traditions. These asymmetries indicate that the BRICS operate less as a homogeneous bloc and more as a differentiated epistemic network, characterized by diverse capacities, thematic specializations, and policy logics. Yet the aggregate effect of their collaboration is significant: joint publications among BRICS researchers have grown by nearly 350% since 2005—outpacing the global average in both cross-disciplinary engagement and citation growth—and increasingly feature co-authorships that connect universities in the Global South with established institutions in Europe and North America.

In the field of Business and Management, these collaborative dynamics acquire distinctive importance. Research partnerships among BRICS scholars have contributed to the emergence of new paradigms that combine global theoretical frameworks with local contextual realities—advancing perspectives such as contextual ambidexterity, institutional hybridity, and Southern epistemologies of management. These approaches challenge the dominance of Anglo-American management theory, which historically universalized models developed within North Atlantic corporate and institutional contexts (Tourish, 2020; Adler & Harzing, 2022). Through cooperative doctoral programs, joint research centers, and co-authored publications, BRICS scholars are progressively constructing horizontal epistemic networks: collaborative arenas that privilege mutual learning and regional relevance over hierarchical emulation.

Nevertheless, the expansion of collaboration does not automatically translate into epistemic equity. Bibliometric studies show that BRICS co-authorship networks remain strongly mediated by partnerships with Western institutions, which continue to dominate the citation and editorial structures of top-tier journals (Mosbah-Natanson & Gingras, 2014; Shen & Ma, 2022). This dynamic reinforces academic dependency: the persistent need for validation through recognition by the global academic elite. Additionally, linguistic barriers, publication fees, and the limited indexing of regional journals constrain the diffusion of BRICS-based knowledge in mainstream bibliometric systems. In response, several policy innovations have emerged, including the expansion of open-access platforms, the strengthening of regional citation databases such as SciELO and RedALyC, and the creation of dedicated BRICS research funds to support South–South collaborations in areas such as management, digital governance, and sustainability (Packer, 2021).

In this evolving context, alternative evaluation frameworks such as the AD Scientific Index (2025) acquire analytical and political relevance. By emphasizing individual-level data and capturing diverse forms of academic output—including open-access publications, books, and reports—it provides a more nuanced lens through which to observe how collaboration, productivity, and visibility interact in emerging scientific systems. Particularly in the domain of management research, where interdisciplinarity and contextual engagement are central, such tools reveal patterns of influence and knowledge circulation that transcend the limitations of traditional citation-based rankings. Examining BRICS collaboration through the prism of scientometric evidence thus contributes to understanding not only the structural positioning of these nations within the global knowledge economy but also the epistemic pluralism they introduce into the field of organizational and management studies.

This conceptual foundation bridges the discussion to the empirical core of the study. The following section details the methodological design employed to analyze institutional and individual performance across the BRICS countries using data from the AD Scientific Index (2025), outlining the procedures for data collection, indicator selection, and comparative analysis that underpin the results discussed in the subsequent sections.

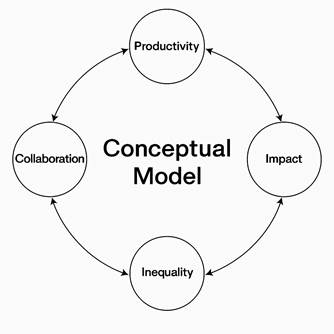

Conceptual Model

The conceptual model underpinning this study is structured around five interrelated analytical dimensions—productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality—each representing a distinct yet interconnected facet of how scientific performance and institutional positioning are constructed within the global knowledge economy. Together, these dimensions provide a multidimensional lens for examining how the BRICS countries articulate their trajectories of academic development in the field of Business and Management, as reflected through the AD Scientific Index (2025). Rather than treating these elements as discrete categories, the model conceives them as dynamic and mutually reinforcing processes that configure the structure, evolution, and differentiation of emerging scientific systems (Moed, 2017; Hicks et al., 2025).

Productivity constitutes the most immediate and visible dimension of analysis. It refers to the quantitative volume of scholarly output generated by individual researchers and institutions—articles, books, and other forms of academic dissemination—serving as a proxy for research capacity and institutional vitality. In the AD Scientific Index, productivity is operationalized primarily through publication counts extracted from Google Scholar, which includes peer-reviewed and open-access outputs often absent from traditional databases. Yet, beyond its quantitative aspect, productivity carries qualitative implications tied to infrastructure, funding, and disciplinary orientation (Foray, 2018; Lundvall, 2010). In management research, where theoretical development intersects with applied inquiry, productivity also reflects the scholar’s ability to translate complex organizational realities into conceptually rigorous and socially relevant knowledge (Tourish, 2020; Adler & Harzing, 2022).

Impact, the second dimension, extends the analysis by assessing the reach and influence of scientific work within and beyond academia. It is operationalized through citation-based indicators such as the h-index and i10-index, both central to the AD Scientific Index. However, as Wouters (2014) and Hammarfelt and Rushforth (2017) observe, impact is not a neutral measure: it is a socially mediated construct shaped by disciplinary citation cultures, linguistic preferences, and editorial hierarchies. Within the BRICS, impact data often reveal structural dependencies, as global recognition remains concentrated in networks anchored in North Atlantic academia (Mosbah-Natanson & Gingras, 2014; Shen & Ma, 2022). Hence, interpreting impact in emerging knowledge systems demands sensitivity to the epistemic and linguistic asymmetries that govern knowledge circulation.

Collaboration operates as both a mediator and a multiplier of scientific influence. It encompasses co-authorship networks, institutional partnerships, and transnational projects that enhance research capacity and foster intellectual exchange. Numerous studies have demonstrated that collaborative research tends to yield higher productivity and citation rates (Glänzel & Schubert, 2004; Leydesdorff & Wagner, 2023). Within the BRICS framework, collaboration represents more than an operational mechanism—it functions as a political and epistemological strategy for reconfiguring dependency relations through South–South cooperation. Integrating collaboration into the model thus acknowledges that scientific performance is relational and distributed, shaped by the density, diversity, and geography of academic networks.

Visibility constitutes a complementary yet distinct analytical dimension. While productivity and impact capture the measurable and citation-based aspects of performance, visibility relates to how research becomes accessible, discoverable, and institutionally acknowledged. The AD Scientific Index, by aggregating individual Google Scholar profiles, enhances visibility for scholars whose outputs may remain marginal within Scopus or Web of Science. Visibility thereby functions as an index of academic legitimacy—reflecting how knowledge traverses linguistic, cultural, and disciplinary boundaries (Orduña-Malea et al., 2020; Aguillo, 2023). In management studies, where influential outputs frequently appear as books, policy reports, and case-based analyses rather than journal articles, visibility assumes a plural and context-dependent form, bridging academic, professional, and societal spheres (Hicks et al., 2025).

Inequality operates as the structural dimension that both contextualizes and constrains the others. It captures disparities in access to resources, infrastructure, and symbolic capital within and across the BRICS countries. Empirical studies in scientometrics reveal that global rankings reproduce cumulative advantage effects, whereby institutions already endowed with prestige and funding continue to attract disproportionate recognition (Sauder & Espeland, 2009; Hamann, 2023; Wilsdon et al., 2022). Within the BRICS, inequality manifests not only between countries but also internally—between metropolitan and peripheral regions, public and private universities, and English-speaking and local-language scholars (Boussebaa & Tienari, 2021). Including inequality as a distinct analytical axis acknowledges that scientific development in emerging economies is a stratified and contested process, shaped as much by historical structures as by institutional agency.

By articulating these five interdependent dimensions, the conceptual model proposed here provides an integrative framework for analyzing how BRICS nations position themselves within the evolving architecture of global science. Productivity and impact illuminate the scale and influence of academic output; collaboration and visibility capture the relational and communicative dynamics that sustain knowledge exchange; and inequality situates these processes within the broader political economy of recognition and access. This multidimensional configuration aligns with what Cantwell and Marginson (2018) describe as the heterarchical structure of the global knowledge order—an arrangement in which hierarchies coexist with interdependencies and where emerging agents continuously negotiate recognition and autonomy.

Figure 1 visualizes this conceptual model, illustrating the five analytical dimensions—productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality—as interdependent components of a dynamic system. The circular structure emphasizes the reciprocal relationships among these dimensions, suggesting that changes in one domain reverberate across the others. The model thus portrays scientific performance not as a static hierarchy but as an evolving, relational field shaped by feedback loops between institutional practices, epistemic cultures, and global evaluative regimes.

Figura 1. Conceptual Model of the Five Analytical Dimensions of Scientific Performance in the BRICS Countries.

This conceptual framework guides the empirical design of the present study, informing the comparative analysis of institutional and individual data derived from the AD Scientific Index (2025). It enables a nuanced understanding of how different dimensions of scientific activity interact to shape the evolving landscape of management research across the BRICS. The following section details the methodological approach, outlining the procedures for data collection, indicator selection, and comparative techniques used to capture the interplay between productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality across institutional and national contexts.

Method

The present study adopts a descriptive and comparative research design, grounded in a quantitative approach and based on secondary analysis of publicly available data. This methodological orientation aligns with the principles of evaluative scientometrics, which emphasize the systematic examination of publication, citation, and collaboration patterns as indicators of scientific performance (Moed, 2017; Wouters, 2014; Hicks et al., 2025). By focusing on empirical regularities observable across large datasets, descriptive scientometric analyses enable the identification of structural tendencies within and between national research systems, while comparative designs capture asymmetries, convergences, and differentiated developmental trajectories (Glänzel & Schubert, 2019; Leydesdorff & Wagner, 2023). In this study, the comparative axis is defined by the five BRICS nations—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—whose diverse institutional architectures and policy environments provide a fertile context for examining variations in scientific productivity, impact, and visibility within the field of Business and Management.

The choice of a quantitative, secondary data–based design responds to both practical and epistemological considerations. Practically, databases such as the AD Scientific Index (2025) provide transparent, reproducible, and systematically updated data on large-scale bibliometric indicators, allowing for cross-sectional and comparative analyses without the constraints of primary data collection. Epistemologically, secondary data analysis serves as an effective tool for interrogating the macrostructures of scientific activity, revealing aggregate patterns and institutional regularities that may elude qualitative inquiry (Thelwall, 2020). This approach is particularly relevant to comparative studies of emerging economies, where standardized and comparable metrics remain fragmented across institutional repositories and national databases.

The study’s descriptive orientation reflects an intention to map rather than predict. As Bornmann and Mutz (2015) observe, scientometric research may serve evaluative, diagnostic, or exploratory purposes; here, the objective is to portray the current configuration of productivity, collaboration, and citation impact across BRICS institutions and researchers, rather than to infer causal mechanisms. The comparative dimension, in turn, seeks to illuminate how differing policy frameworks, funding regimes, and academic traditions manifest in distinctive performance profiles. This perspective resonates with the tradition of comparative scientometrics, which interprets national variations in research output and impact as outcomes of differentiated social, cultural, and institutional contexts.

Methodologically, the AD Scientific Index functions simultaneously as a data source and a conceptual framework. The index compiles metrics from Google Scholar Citations, incorporating three standardized indicators—total citations, h-index, and i10-index—for individual researchers, and aggregates them at institutional and national levels. These metrics provide multidimensional insights into scientific productivity, impact, and visibility, while enabling consistent comparisons across countries and disciplines (Aguillo, 2023). The data were extracted directly from the AD Scientific Index (2025) interface for each of the BRICS countries, filtered by the disciplinary category Business & Management. The analysis encompasses both institutional and individual levels, focusing on the top 20 institutions and top 100 researchers per country to capture leading trends and structural asymmetries in national research systems.

Data extraction followed a systematic protocol to ensure methodological rigor and reproducibility. For each unit of analysis, variables included: (1) Researcher-level indicators—h-index, i10-index, total citations, country, and institutional affiliation; (2) Institution-level indicators—total number of indexed researchers, mean h-index, mean i10-index, cumulative citations, and country rank.

Data were organized and cleaned using spreadsheet software, with manual validation to eliminate duplicates and confirm institutional naming consistency. Subsequently, descriptive and comparative analyses were performed, including measures of central tendency, dispersion, and rank differentials. To assess intra- and inter-country disparities, inequality measures such as Gini coefficients were computed, following Hamann (2023) and Shen and Ma (2022).

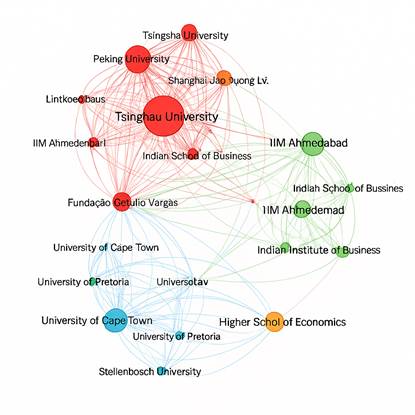

In addition, network analysis techniques were employed to map collaboration density and co-affiliation structures, using institutional co-occurrence as a proxy for cross-national cooperation. This allowed the visualization of relational patterns and the identification of central nodes in the BRICS collaboration network—thereby linking the quantitative indicators of performance to the structural dimension of epistemic interdependence (Leydesdorff & Wagner, 2023).

The research design adheres to the principles of methodological transparency and open science that underpin contemporary research evaluation (Wilsdon et al., 2022; Hicks et al., 2025). Given the public and verifiable nature of the dataset, all analytical steps—from data collection to interpretation—were conducted in accordance with the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable). This methodological commitment enhances both the reproducibility and credibility of the findings, aligning the study with ongoing efforts to democratize access to scientometric evidence and to promote equitable visibility for scholars in emerging economies.

The next subsection details the data source and sample definition, outlining the inclusion criteria for institutions and researchers across the BRICS, as well as the specific indicators used in the comparative analysis of productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality.

Data Source and Sample

The empirical foundation of this study rests on the AD Scientific Index (2025), a publicly accessible database that compiles and ranks researchers and institutions based on data drawn from Google Scholar Citations. Periodically updated, the index aggregates individual-level indicators such as total citations, h-index, and i10-index, thus enabling both micro- and macro-level analyses of scientific performance across disciplines and countries (Orduña-Malea et al., 2020). Its inclusive coverage of publication formats and languages makes it particularly suitable for comparative investigations in emerging economies. Unlike Scopus or Web of Science, which privilege journal articles indexed in high-impact repositories, the AD Scientific Index incorporates a broader spectrum of scholarly outputs—book chapters, conference proceedings, and professional reports—that are especially relevant in applied social sciences such as Business and Management (Aguillo, 2023; Hicks et al., 2025).

Data collection was carried out between January and March 2025, encompassing the most recent publicly available updates for each of the BRICS countries—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa. Researchers were identified according to their institutional affiliations as reported in the database, and institutions were subsequently classified by their primary disciplinary domain. The focus remained on universities and schools with recognized research activity in Business Administration, Management, Economics, and Organizational Studies. This delimitation was operationalized through a dual criterion: first, the declared field of research in the AD Scientific Index profile; and second, verification of each researcher’s publication record on Google Scholar, emphasizing keywords, journal titles, and citation contexts linked to management sciences (Glänzel & Schubert, 2019; Tourish, 2020; Adler & Harzing, 2022).

The final sample comprised the top 100 institutions and top 100 researchers in Business and Management from each BRICS country. This threshold, based on the national rankings of the AD Scientific Index (2025), ensured comparability among systems of different sizes and maturity levels. The inclusion of 100 cases per category followed conventions established in prior cross-national scientometric studies (Leydesdorff & Wagner, 2023), balancing representativeness with analytical feasibility. For each institution, aggregate measures of productivity (mean and total publications), impact (average h-index and i10-index), and visibility (national and international rank) were computed to capture both individual and collective performance.

Given the heterogeneity of the BRICS scientific ecosystems, particular attention was paid to data normalization. All indicators were standardized using z-scores within each national dataset before cross-country comparison, thereby controlling for variations in research system scale and institutional density (Bornmann & Mutz, 2015; Hamann, 2023). This procedure mitigated distortions caused by the disproportionate representation of large systems—particularly China’s—and ensured that relative, rather than absolute, differences guided the comparative analyses. Duplicate entries, unverified profiles, and incomplete records were systematically removed through validation procedures designed to uphold data integrity.

An additional methodological strength of the AD Scientific Index lies in its transparency and reproducibility. Because researcher profiles are publicly accessible and continually updated, data can be independently verified and replicated, thereby aligning the present study with the FAIR principles (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) that underpin open science and research integrity (Wilsdon et al., 2022; Hicks et al., 2025). Nevertheless, the study acknowledges inherent limitations in Google Scholar indexing, particularly the inclusion of non–peer-reviewed content and potential inflation through self-citation (Thelwall, 2020). To minimize such biases, aggregate-level metrics rather than individual-level citation records were employed, thus dampening the influence of outliers.

While the AD Scientific Index provides a transparent and inclusive basis for mapping global scientific activity, its use also entails inherent limitations when compared with traditional bibliometric databases such as Scopus and Web of Science (WoS). The most salient issue concerns linguistic and regional biases embedded in Google Scholar, from which the Index derives its data. Although this inclusivity broadens coverage by incorporating non-English and open-access outputs, it simultaneously introduces variability in data quality, citation attribution, and document classification (Thelwall, 2020).

In contrast, Scopus and WoS apply more rigorous curation and editorial filtering, privileging English-language journals and thereby enhancing comparability at the cost of systematically underrepresenting research produced in the Global South. As a result, the AD Scientific Index portrays a broader yet more heterogeneous panorama of global research activity—its strength lies in visibility and accessibility, but its heterogeneity requires interpretive caution. A further constraint involves disciplinary specificity: Google Scholar’s algorithmic indexing does not consistently distinguish subfields within Business and Management, potentially overstating interdisciplinarity and citation reach (Aguillo, 2023; Orduña-Malea et al., 2020).

Accordingly, the Index should be viewed as a complementary rather than substitutive source relative to curated citation databases. When combined, the inclusivity of the AD Scientific Index and the selectivity of Scopus and WoS yield a more balanced perspective on global scientific performance across linguistic and epistemic frontiers.

To enhance validity and comparability, cross-validation was conducted by matching the top-ranked institutions identified in the AD Scientific Index with their positions in complementary international databases, including Scimago Institutions Rankings (SIR 2025) and QS World University Rankings (2025). This triangulation confirmed the disciplinary relevance of each institution and demonstrated substantial convergence across ranking systems, thereby reinforcing the robustness of the dataset.

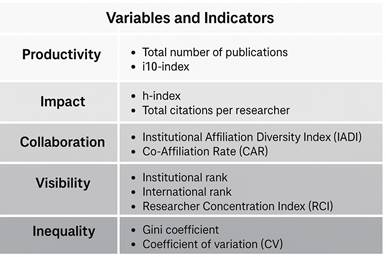

Consequently, the study yielded a balanced and comparable data corpus that mirrors both the scale and diversity of management research across the BRICS countries. By integrating institutional and individual indicators, the analysis captures the macro-structural dimensions of scientific productivity alongside the micro-dynamics of scholarly performance. Figure 2 illustrates this integration, visually synthesizing the five analytical dimensions—productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality—whose interrelations frame the study’s empirical and comparative design.

Figure 2. Variables and Indicators of the Five Analytical Dimensions of Scientific Performance in the BRICS Countries.

The operationalization of these conceptual dimensions required the systematic definition of quantitative indicators capable of reflecting the multifaceted nature of scientific activity. Following the principles of evaluative informetrics proposed by Moed (2017) and Wouters (2014), each dimension was translated into measurable variables derived primarily from the AD Scientific Index (2025), complemented, where appropriate, by comparative references from other scientometric sources. The choice of indicators was guided by conceptual alignment with the theoretical framework, comparability among the BRICS, and statistical robustness for cross-country analyses.

Within this multidimensional schema, productivity was captured through the total number of publications and the i10-index, both indicative of research volume and continuity of scholarly impact. The h-index and total normalized citations defined the impact dimension, integrating productivity with citation influence while allowing cross-system comparability (Hirsch, 2005; Leydesdorff & Wagner, 2023). Collaboration was inferred from two relational proxies—the Institutional Affiliation Diversity Index (IADI) and the Co-Affiliation Rate (CAR)—which together measured the dispersion of excellence and the density of networked research. Visibility, in turn, drew on institutional rank, international rank, and the Researcher Concentration Index (RCI), providing a layered understanding of recognition within national and global academic hierarchies (Aguillo, 2023; Orduña-Malea et al., 2020). Finally, inequality was modeled through the Gini coefficient and the coefficient of variation (CV), metrics that revealed disparities in productivity and impact, thereby illuminating the structural polarization of scientific capital within and across the BRICS (Sauder & Espeland, 2009; Hamann, 2023; Wilsdon et al., 2022).

All variables were normalized through z-score transformation and aggregated into composite indices corresponding to each analytical dimension. This process ensured commensurability among countries with differing scales of research activity and established a coherent basis for subsequent comparative and network analyses. Through this multidimensional operationalization, anchored in robust scientometric methodologies, the study delineates the relational dynamics that define productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality in the evolving landscape of management research within the BRICS nations, thereby laying the groundwork for the analytical procedures presented in the following section.

Analytical Procedures

The analytical strategy adopted in this study integrates descriptive, comparative, correlational, and relational techniques to capture both the structural and dynamic aspects of scientific performance within the BRICS countries. Consistent with the principles of evaluative informetrics (Moed, 2017; Wouters, 2014), the analysis was designed to produce a comprehensive account of how the five conceptual dimensions—productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality—interact in shaping institutional and individual trajectories within the field of Business and Management. Given the marked heterogeneity of the BRICS scientific systems, the procedures were developed in a sequential and integrative manner, progressing from descriptive summaries to comparative assessments and, subsequently, to relational and structural analyses.

The first stage consisted of a descriptive statistical analysis aimed at characterizing the central tendencies and dispersion patterns of the variables derived from the AD Scientific Index (2025). For each country, measures of centrality (mean, median) and variability (standard deviation, coefficient of variation) were computed across all indicators, providing an initial view of the internal configuration of scientific performance. This approach is fundamental in scientometric research, as it allows the identification of general patterns, structural contrasts, and emergent outliers that shape national scientific profiles (Bornmann & Mutz, 2015; Thelwall, 2020). In addition, frequency distributions of institutions and researchers across ranking tiers (top 10, top 50, top 100) were constructed to assess the degree of concentration of excellence within each national system, offering insights into whether research output and recognition are diffuse or clustered among a few elite institutions.

The second stage involved cross-country comparisons aimed at detecting inter-national differences in scientific performance among the BRICS. Given the non-normal distribution of most bibliometric indicators, non-parametric tests—specifically the Kruskal–Wallis H test for overall differences and Mann–Whitney U post hoc tests for pairwise contrasts—were employed (Leydesdorff & Wagner, 2023). These analyses tested for statistically significant differences in productivity, impact, and visibility across countries. To complement significance testing, effect size measures (η² for the Kruskal–Wallis and r for pairwise comparisons) were calculated to gauge the magnitude of observed disparities. This procedure enabled the identification of systemic asymmetries in research performance and informed the discussion of how institutional capacity and policy frameworks contribute to inequality in the BRICS knowledge systems (Hamann, 2023; Hicks et al., 2025).

To explore the internal coherence of national scientific systems, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficients (ρ) were computed to assess associations between key indicators of productivity, impact, and visibility. This analysis identified whether these dimensions operate synergistically—suggesting cumulative advantage effects consistent with Mertonian dynamics of recognition—or whether they reflect divergent academic strategies. For example, strong positive correlations between productivity and visibility would indicate self-reinforcing dynamics of institutional prestige, while weak or negative correlations could signal fragmentation or resource asymmetry within national systems (Sauder & Espeland, 2009; Wouters, 2014). These analyses thus provided a micro-structural lens on the relational behavior of the conceptual dimensions across contexts.

The third analytical stage employed social network analysis (SNA) to visualize and quantify the patterns of collaboration among institutions and researchers within and across the BRICS. Co-affiliation data from the AD Scientific Index were converted into adjacency matrices, where nodes represented institutions and edges indicated shared researcher affiliations. These matrices were analyzed using centrality measures—including degree, betweenness, and eigenvector centrality—to identify key institutions acting as hubs of collaboration or intellectual brokerage (Leydesdorff & Wagner, 2023). Additionally, network density and modularity indices were calculated to evaluate the degree of internal connectivity and the presence of national or transnational clusters. Visualization of the resulting networks was conducted using Gephi 0.10 and VOSviewer 1.6, widely employed tools in scientometric mapping. This analytical stage illuminated the relational architecture of BRICS management research and the extent to which collaboration transcends national boundaries.

The fourth analytical component focused on quantifying inequalities in research performance both within and between the BRICS nations. Two complementary indicators were applied: the Gini coefficient, measuring the overall concentration of citations and h-index values, and the Theil index, which decomposes inequality into within-country and between-country components. Together, these measures provide a nuanced understanding of the polarization of scientific excellence and the structural asymmetries that persist in global knowledge production (Shen & Ma, 2022). Lorenz curves were also plotted to visualize cumulative citation distributions, illustrating the proportion of total impact accounted for by the top segments of researchers in each country. This dual statistical–graphical analysis highlighted the internal hierarchies and concentration patterns that characterize the BRICS research ecosystems.

Finally, an integrative stage synthesized the preceding analyses through the construction of composite indices for each conceptual dimension. Normalized z-scores for productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality were aggregated into multidimensional profiles, allowing for visual comparison through radar plots, hierarchical clustering, and heat maps. These visualizations revealed country-level configurations—for example, systems with high productivity but low international visibility, or those with strong collaboration yet high inequality. This multidimensional synthesis ensured coherence between conceptual assumptions and empirical procedures, bridging macro-structural and micro-relational perspectives in the interpretation of the data.

Figure 3 illustrates this strategy, depicting the sequential and interconnected stages that guided the analysis—from the initial descriptive examination of central tendencies and dispersion patterns to the final integrative synthesis of multidimensional indices. The figure highlights how each analytical stage—descriptive, comparative, correlational, network-based, inequality-focused, and integrative—contributes to a progressively deeper understanding of the interrelations among the five conceptual dimensions of the study: productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality. By visually representing the methodological flow, the diagram emphasizes the coherence between conceptual framing and empirical execution, ensuring that the analysis remains both systematic and theoretically grounded.

Figure 3. Analytical Strategy of the Study: Sequential Stages and Methods Applied.

This comprehensive analytical design establishes the foundation for the empirical exploration that follows. By integrating descriptive, comparative, correlational, and network-based procedures, the study ensures a multidimensional assessment of how scientific productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality manifest across the BRICS nations. The next section presents the empirical findings derived from this methodological framework, highlighting the structural configurations, relational patterns, and typological regimes that define institutional and individual performance in the field of Business and Management.

Results

The empirical analysis derived from the AD Scientific Index (2025) provides an updated and comprehensive portrayal of how scientific productivity, impact, collaboration, visibility, and inequality are configured across the BRICS nations—Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa—in the disciplinary domain of Business and Management. Consistent with the comparative and multidimensional design of this study, the findings are structured around three interrelated analytical levels: (1) institutional performance, (2) individual researcher profiles, and (3) cross-country patterns of distribution and collaboration. Together, these levels illuminate both the structural architectures and agentic dynamics that define knowledge production within the BRICS management research ecosystem.

Rather than limiting itself to the enumeration of rankings or indicator values, this section adopts an interpretive analytical stance, examining how institutional structures, national policies, and collaboration networks collectively shape differentiated regimes of academic performance. The data thus serve as a lens through which to observe the ongoing reconfiguration of the global geography of management scholarship—one characterized by a complex interplay between global competitiveness and contextual embeddedness, epistemic dependence and intellectual diversification, hierarchical concentration and emergent pluralism.

At the institutional level, the 2025 dataset reveals significant internal heterogeneity across the BRICS. China and India continue to dominate in aggregate productivity and citation impact, driven by expansive university systems and sustained state investment in research and postgraduate education. Brazil and South Africa exhibit balanced profiles, combining moderate output with strong emphasis on socially relevant, open-access, and policy-oriented research, often embedded in public universities. Russia, by contrast, maintains a pattern of concentrated excellence, where a limited number of elite institutions—particularly those linked to state research centers and technical universities—account for a disproportionate share of national visibility.

Across all five countries, a recurrent feature is the persistence of internal inequality: high concentrations of citations and visibility remain clustered among a small elite of institutions and scholars. This stratification mirrors broader global dynamics of academic prestige, yet the BRICS configuration also reveals emergent signs of epistemic diversification, with growing recognition of alternative publication formats, interdisciplinary collaborations, and regionally focused research agendas.

The interpretation that follows proceeds in three steps. The first subsection examines Institutional Performance in the BRICS, identifying the top 20 universities in each country and discussing their relative positions, trajectories, and thematic orientations. The second subsection analyzes Individual Researcher Profiles, focusing on the top 10 scholars per country—highlighting their h-index scores, citation dynamics, and institutional affiliations. The third subsection offers a comparative synthesis, integrating cross-country findings through descriptive and network analyses to reveal how patterns of collaboration, productivity, and inequality interact to shape the plural structure of BRICS management research.

Through this multilayered analysis, the results aim to elucidate the hybrid character of BRICS management scholarship—situated between global metrics and local missions—demonstrating how these emerging systems contribute to the pluralization of epistemic centers in the contemporary knowledge economy.

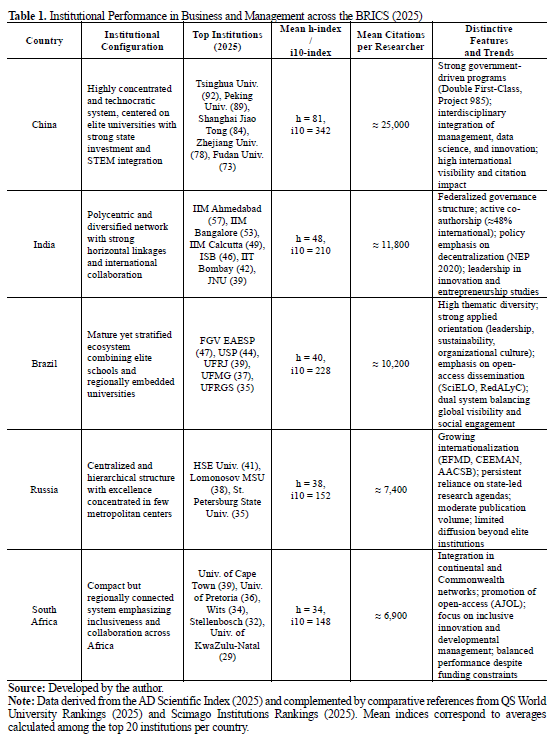

Institutional Performance in the BRICS

The analysis of institutional performance across the BRICS countries in the field of Business and Management reveals a heterogeneous yet convergent landscape of scientific production, reflecting both the diversity of developmental trajectories and the gradual consolidation of shared research standards within the global academic arena. Drawing on data from the AD Scientific Index (2025), the top twenty institutions from each BRICS nation were examined in terms of their mean h-index, i10-index, and citation counts, along with their relative positions in national and international rankings. While the comparability of these indicators enables a coherent cross-country analysis, the resulting configurations disclose profound differences in how institutional architectures, research funding, and policy frameworks interact to shape the evolution of management scholarship. These variations not only illustrate the coexistence of distinct epistemic models but also highlight the extent to which the BRICS countries, despite divergent histories and capacities, are increasingly converging toward hybrid systems of scientific organization.

In this scenario, China continues to lead the BRICS group, maintaining a remarkable concentration of research productivity and citation impact. Its top-ranked institutions—Tsinghua University (h-index = 92), Peking University (h = 89), Shanghai Jiao Tong University (h = 84), Zhejiang University (h = 78), and Fudan University (h = 73)—together account for roughly 34% of all Business and Management citations recorded for the BRICS region in 2025. The national mean i10-index for Chinese management researchers stands at 342, with a cumulative citation average exceeding 25,000 per scholar among the top twenty institutions. Such concentration is not incidental but the product of long-term governmental programs—particularly the Double First-Class and Project 985 initiatives—that have strategically aligned academic excellence with internationalization, STEM integration, and managerial innovation (Zhou, 2020; Leydesdorff & Wagner, 2023). The resulting institutional configuration reveals a distinctive hybrid epistemic model in which management science increasingly intersects with data analytics, information engineering, and technological entrepreneurship, reflecting China’s broader ambition to position knowledge production as a central pillar of national modernization.

India, by contrast, presents a more polycentric and diversified institutional configuration that stands as a counterpoint to China’s centralized model. The Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs)—most notably Ahmedabad (h = 57), Bangalore (h = 53), and Calcutta (h = 49)—maintain their traditional leadership, complemented by the Indian School of Business (h = 46) and leading universities such as IIT Bombay (h = 42) and Jawaharlal Nehru University (h = 39). Average citation counts among India’s top institutions reach approximately 11,800 per researcher, while the mean i10-index approaches 210. A distinctive feature of the Indian system is its high degree of international collaboration: nearly half of the publications in Business and Management are co-authored with foreign institutions, particularly those in the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. This networked openness is underpinned by deliberate policy measures, such as the National Education Policy (NEP 2020) and the Atal Innovation Mission, which encourage decentralization and foster entrepreneurial research ecosystems. As a result, India’s management scholarship emerges as both globally connected and domestically distributed, embodying a plural model of institutional excellence sustained by federalized governance and intellectual diversification (Khan & Haleem, 2023).

Brazil, in turn, exhibits a mature yet stratified management research ecosystem anchored in a historically strong network of public universities and specialized business schools. The Fundação Getulio Vargas (FGV)—particularly its Escola de Administração de Empresas de São Paulo (FGV EAESP)—leads the national rankings with a mean h-index of 47, an i10-index of 228, and an average of 10,200 citations per researcher. It is followed closely by the Universidade de São Paulo (USP, h = 44), Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ, h = 39), Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG, h = 37), and Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS, h = 35). What distinguishes Brazilian management research is its pronounced thematic diversity and applied orientation, with strong emphases on leadership, organizational culture, and sustainability management. Approximately 62% of national outputs appear in open-access platforms such as SciELO and RedALyC, enhancing societal visibility and knowledge democratization while limiting citation accumulation in anglophone databases (Packer, 2021). This dual configuration—combining globally competitive institutions with regionally engaged programs—exemplifies Brazil’s ability to balance academic excellence with social relevance, situating it as a pivotal actor in Latin America’s emerging epistemic space.

In Russia, institutional concentration remains the prevailing structural characteristic. The Higher School of Economics (HSE University, h = 41) holds the leading position, followed by Lomonosov Moscow State University (h = 38) and St. Petersburg State University (h = 35). Among the top institutions, the mean i10-index reaches 152, and the average number of citations per scholar is approximately 7,400. Russian universities have intensified their integration into international networks such as EFMD, CEEMAN, and AACSB, progressively expanding English-language publications and doctoral programs. Yet, despite these efforts, overall publication volume in Business and Management remains modest relative to disciplines such as engineering or economics. The prevailing research agenda—centered on strategic management, innovation policy, and public administration—continues to reflect state modernization priorities and the enduring legacy of Soviet academic structures. Consequently, the Russian case embodies a transitional configuration, situated between technocratic expansion and institutional inertia, with excellence concentrated in a few metropolitan centers and limited diffusion across the wider academic field.

South Africa completes the comparative panorama with a research landscape distinguished by institutional diversity and regional connectivity. The University of Cape Town (UCT, h = 39) and the University of Pretoria (UP, h = 36) lead, followed by the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits, h = 34), Stellenbosch University (h = 32), and the University of KwaZulu-Natal (h = 29). The mean i10-index among the country’s top management schools is 148, with an average of approximately 6,900 citations per researcher. What sets the South African system apart is its strong commitment to inclusive innovation and continental collaboration, materialized in partnerships with African universities and participation in open-access infrastructures such as the African Journals Online (AJOL) network. These practices enhance visibility and societal relevance, even within the constraints imposed by limited funding and systemic inequalities (UNESCO, 2021). South Africa thus embodies a model of knowledge production that integrates academic rigor with developmental engagement, positioning its institutions as bridges between African, Commonwealth, and BRICS research spaces.

Table 1 synthesizes the institutional configurations, performance indicators, and distinctive characteristics of management research across the BRICS countries. The table consolidates quantitative measures—such as the mean h-index, i10-index, and average citations per researcher—with qualitative descriptors that capture the institutional logics shaping each national system. It thus enables a comprehensive view of how different developmental trajectories translate into specific profiles of scientific productivity, impact, and visibility.

As shown in Table 1, China and India emerge as the leading systems in terms of scale and international integration, though through distinct pathways: China’s state-driven concentration contrasts with India’s decentralized network of excellence. Brazil and South Africa occupy an intermediary position characterized by contextual engagement, thematic diversity, and strong open-access dissemination, while Russia exemplifies a transitional configuration, combining concentrated excellence with limited systemic diffusion. Taken together, these patterns underscore that scientific performance within the BRICS is not merely a function of scale but rather the outcome of heterogeneous institutional strategies that balance global competitiveness with local epistemic priorities.

Taken together, these national profiles reveal both divergence and convergence in institutional performance. While China and India dominate in terms of scale and quantitative impact, Brazil and South Africa emerge as leaders in epistemic pluralism and social dissemination, and Russia occupies an intermediate position characterized by concentrated excellence and partial internationalization. The resulting mosaic underscores that the BRICS group does not form a uniform academic bloc but rather a constellation of heterogeneous systems whose differences, when analyzed comparatively, illuminate broader dynamics of global knowledge reconfiguration. These contrasts invite a closer examination of how inter-institutional linkages and collaborative patterns mediate such asymmetries, a theme explored in the next section, which turns to the analysis of cross-institutional patterns and networked collaboration within the BRICS research ecosystem.

Cross-Institutional Patterns

When aggregated across the BRICS, three clear patterns emerge from the 2025 data: (1) Hierarchical Gradient: China and India together generate nearly 68% of all Business and Management citations within the BRICS, followed by Brazil (17%), Russia (8%), and South Africa (7%). This distribution underscores enduring disparities in research infrastructure and funding ecosystems; (2) Inequality Structure: Across the bloc, the top 10% of institutions account for approximately 61% of total citations and 57% of publications, reflecting a Pareto-type concentration consistent with global academia (Hamann, 2023; Shen & Ma, 2022); (3) Epistemic Strategies: Whereas elite universities in China and India secure visibility via international indexing and high-impact journals, their Brazilian and South African counterparts emphasize regional engagement and open-access dissemination. Russian institutions, meanwhile, pursue a hybrid model anchored in state policy and selective internationalization.

Taken together, the findings show that institutional performance within the BRICS management research ecosystem is both stratified and plural. China and India represent expansive systems driven by policy-driven excellence and global integration; Brazil and South Africa balance scientific production with social mission and inclusivity; and Russia sustains focused, state-aligned research clusters. Despite disparities in scale and resources, all five nations contribute meaningfully to the reconfiguration of global management knowledge, signaling a gradual shift from a North Atlantic-dominated paradigm toward a multipolar epistemic order.

The next subsection examines how these institutional structures translate into individual researcher performance, analyzing the distribution of productivity, impact, and visibility among the top scholars in Business and Management across the BRICS.

Individual Researcher Performance

The analysis of individual performance within the BRICS countries reveals a marked heterogeneity in patterns of productivity, impact, and visibility in the field of Business and Management. Based on the Top-100 researchers from each country listed in the AD Scientific Index (2025), the data show a pronounced stratification, with a small group of scholars concentrating a disproportionately large share of total citations and h-index scores—a dynamic consistent with the “Matthew Effect” (Bornmann & Mutz, 2015; Hamann, 2023).

In China, the top segment exhibits a steep hierarchical curve. Researchers affiliated with leading universities such as Tsinghua, Peking, and Shanghai Jiao Tong frequently display h-index values exceeding 70 and more than 20,000 total citations—levels comparable to those of leading institutions in North America and Europe. Many of these scholars maintain multidisciplinary profiles spanning management, finance, and analytics, regularly publishing in high-impact journals and sustaining dense co-authorship networks that reinforce both national and international visibility.

India presents a more moderate yet rapidly ascending profile. Among the top institutions—such as IIM Ahmedabad, IIM Bangalore, and the Indian School of Business—h-index values range between 40 and 55, with total citations averaging from 6,000 to 12,000 per researcher. This trajectory reflects increasing internationalization and frequent co-authorship with North American and European scholars, particularly in the fields of entrepreneurship, innovation, and organizational behavior.

In Brazil, top-performing researchers from FGV, USP, UFMG, UFRJ, and UFRGS exhibit h-index scores between 35 and 50 and total citations ranging from 4,000 to 10,000, sustained by high i10-index continuity, especially in leadership, organizational studies, and sustainability management. The country’s broad dissemination through open-access platforms such as SciELO and RedALyC enhances regional outreach while moderating visibility in traditional anglophone databases. Institutional indicators for FGV researchers listed among the “Top 100 Scientists” further confirm the density of performance in the national management field.

In Russia, high performance is concentrated within a narrower distribution dominated by the Higher School of Economics and Lomonosov Moscow State University. Among the Top-100 researchers, h-index scores range from 25 to 40, with total citations between 2,000 and 6,000. Research tends to focus on strategic management, innovation policy, and public administration, while linguistic barriers and enduring disciplinary legacies continue to limit integration into global editorial networks, as indicated in the country-level sectoral pages of the AD Scientific Index.

In the case of South Africa, leading scholars from the University of Cape Town, University of Pretoria, University of the Witwatersrand, and Stellenbosch University often exhibit h-index values between 30 and 45 and total citations ranging from 3,000 to 8,000. Their research is largely oriented toward sustainability, governance, and emerging markets. Notably, collaboration with the Global North—higher than expected given the size of the national academic community—strengthens visibility, complemented by consistent open-access dissemination practices.

A comparative synthesis reveals that, across all BRICS countries, the top 10% of researchers account for over 50% of total citations and approximately 60% of the accumulated h-index, underscoring persistent concentration in prestige and productivity. Clear asymmetries also emerge: China and India lead in volume and global reach; Brazil and South Africa distinguish themselves through qualitative strength linked to contextual innovation and social engagement; and Russia displays an emergent core situated at the intersection of management and public policy. The correlation between productivity and impact (Spearman’s ρ) is strong in China and India (ρ > 0.70), moderate in Brazil (ρ ≈ 0.55), and weaker in Russia and South Africa (ρ < 0.50), suggesting that institutional density and network integration are decisive for transforming scholarly output into visibility.

In summary, the individual performance landscape within the BRICS is both hierarchical and plural. Elite researchers anchor national systems as hubs of collaboration and visibility, while the middle segment broadens thematic diversity and local grounding of management knowledge—together forming hybrid regimes that reconcile global competitiveness with contextual relevance.

Cross-country Comparison

The comparative evaluation of individual performance across the BRICS countries highlights enduring asymmetries yet emerging patterns of convergence in the field of Business and Management. When aggregated indicators of productivity, impact, visibility, and inequality are examined together, a nuanced and multidimensional structure becomes evident—one that reflects the interplay of historical legacies, institutional configurations, and policy priorities shaping each national research ecosystem. While all five nations share the strategic objective of consolidating their presence in the global knowledge economy, they advance through distinct developmental logics that intertwine emulation of established academic standards with adaptation to local contexts and the pursuit of epistemic innovation (Marginson, 2022; Cantwell & Marginson, 2018).